한식 읽기 좋은 날

Vol 51. Korean Food that comes from trees

Korea Grand Master No. 77: Moon Wanki (sikhye)

HANSIK Masters

A sip of sikhye (sweet rice punch) offered by Korea Grand Master Moon Wanki initiated a chain reaction in my mouth. The first sensation was the coolness of something that had been just taken out of a refrigerator. This was soon followed by a sweet, savory flavor that lingered in my nose and on my tongue for a while. The final sensation was an aftertaste that, despite the sweetness, was refreshing and not cloying. It brought to mind the sikhye ladled by my grandmother in the summer. I realized that I wanted more. A visit with Moon Wanki opened my eyes to what traditional sikhye is supposed to taste like—delicious!

Article Seo Dongchul (Editorial Team) Photos Lee Daewon (SSSAUNA Studio)

Q. How did Koreans consume sikhye in the past? What effects does sikhye have on the body?

Long ago, sikhye was the equivalent of a digestive aid. On feast days, villagers would gather at someone’s home to help prepare food, and one thing that was always included was sikhye. People would often get stomachaches after eating too much (large amounts of food were not commonly consumed in pre-modern Korea). This was easily addressed with a cup of sikhye, which helps digestion as it is a fermented drink. Sikhye is also known to relieve constipation, prevent intestinal cancer, and alleviate hangovers.

Q. You are very dedicated to making sikhye more recognized internationally. What kinds of sikhye do foreigners prefer? What have you accomplished in this area thus far?

People from countries that are not rice-growing are put off by the appearance of sikhye. Several years ago, I participated in an event in Dubai where I found that people did not like the floating rice grains or the (lack of) color. They asked whether the rice granules are supposed to be there or whether sikhye is a juice or soup. This made me realize the need for a brighter color for our sikhye that, while it may not be as vivid as the color of orange or grape juice, makes it look more appetizing. We also removed the rice so as not to put consumers off. I am currently attending a graduate program at Kyung Hee University. We regularly hold taste-testing sessions for foreign students at the university and the nearby Hankuk University of Foreign Studies to find out which flavors are most popular.

We also drastically extended the shelf life of sikhye, which was a major obstacle to its export. In warmer weather, like we have right now, sikhye can spoil during the production process. In sterilized packaging, however, sikhye can be stored at room temperature for as long as 18 months. This means that sikhye can be exported without having to worry about it spoiling. In 2001, Sejun Food was named as a Competitive Export-Friendly SME of Gyeonggi-do. Since then, we have been sending our products to the US, Japan, China, Canada, and Australia.

China and Japan, which are rice-growing countries, have their own traditional beverages that are similar to sikhye. I feel, however, that they lack the sophistication of sikhye. I’m optimistic about the popularity of Korean culture and products overseas, because this means that people all over the world will soon come to appreciate the taste of sikhye.

Q. Your family has been making sikhye for three generations based on a sikhye recipe included in Somunsaseol, a collection of recipes and ingredients from the late Joseon dynasty.

I have loved sikhye since I was a kid. It was a preference of the heart rather than the brain: sikhye was the first thing that came to mind whenever I wanted a snack. After getting married, I learned that, every summer, my father-in-law went to the market to sell sikhye that he made using a traditional recipe passed down by his mother. A cup of icy sikhye was a popular treat for merchants and customers alike. As I wanted to make this sikhye known to a wider audience, I suggested to my father-in-law that we start a business with it. That was how Sejun Food, a manufacturer of traditional beverages, began. I can’t believe it has already been over 30 years!

It was not easy, by any means, to expand what was previously done in the home with one cauldron into a mid-sized manufacturing business. My father-in-law and I spent a lot of time thinking about the best way to maintain the traditional recipes and flavors while making the sikhye something that can be mass-produced. We collected data on how temperature affects each step of sikhye production per season and developed our own large-scale rice cooker for making over-baked rice. Because we were walking a path never taken before, there was a lot of trial and error. Looking back on those years now, after having been named a Korea Grand Master in 2018, I feel that everything was well worth it.

Q. You are, currently, the only Grand Master whose specialty is sikhye. Is there something about this beverage that explains why there are so few experts on it? What do you think is the most important part of a traditional sikhye recipe?

The sikhye that is currently on the market is sweetened simply by adding enzymes and sugar. However, the sweetness created in this way does not have the depth of flavor of traditional sikhye. This is not a bad thing: I am aware that manufacturers have little other choice if their goal is mass production.

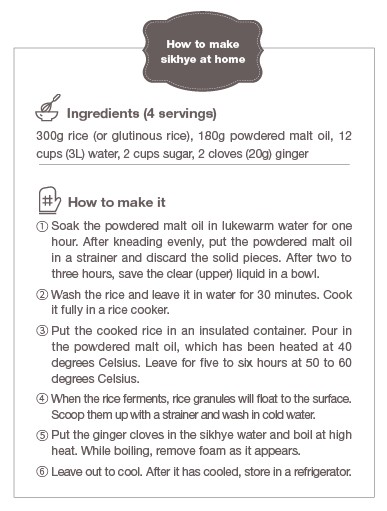

The traditional way of making sikhye requires lots of waiting. Unhulled barley that has just sprouted is dried and then made into powdered malt oil. The water used to boil the barley is allowed to settle for eight hours and then sifted, after which it is combined with over-baked rice and saccharized at 60 degrees Celsius (a process that requires another five or six hours). Sejun Food is the only traditional beverage maker in Korea that owns a large-scale production facility that saccharizes for this long. Every step takes time, which is why we make sikhye only once per day. I wanted to share with consumers the flavors of traditional sikhye and show them how healthy it is—even if that means we cannot mass produce it. The title of Korea Grand Master is something that I believe I received for refusing to compromise on these fundamentals.

Q. You are very dedicated to making sikhye more recognized internationally. What kinds of sikhye do foreigners prefer? What have you accomplished in this area thus far?

People from countries that are not rice-growing are put off by the appearance of sikhye. Several years ago, I participated in an event in Dubai where I found that people did not like the floating rice grains or the (lack of) color. They asked whether the rice granules are supposed to be there or whether sikhye is a juice or soup. This made me realize the need for a brighter color for our sikhye that, while it may not be as vivid as the color of orange or grape juice, makes it look more appetizing. We also removed the rice so as not to put consumers off. I am currently attending a graduate program at Kyung Hee University. We regularly hold taste-testing sessions for foreign students at the university and the nearby Hankuk University of Foreign Studies to find out which flavors are most popular.

We also drastically extended the shelf life of sikhye, which was a major obstacle to its export. In warmer weather, like we have right now, sikhye can spoil during the production process. In sterilized packaging, however, sikhye can be stored at room temperature for as long as 18 months. This means that sikhye can be exported without having to worry about it spoiling. In 2001, Sejun Food was named as a Competitive Export-Friendly SME of Gyeonggi-do. Since then, we have been sending our products to the US, Japan, China, Canada, and Australia.

China and Japan, which are rice-growing countries, have their own traditional beverages that are similar to sikhye. I feel, however, that they lack the sophistication of sikhye. I’m optimistic about the popularity of Korean culture and products overseas, because this means that people all over the world will soon come to appreciate the taste of sikhye.

Q. I understand that you use only domestically-grown ingredients—especially rice and powdered malt oil.

If the ingredients used are of poor quality, no matter how faithfully one adheres to the traditional recipes, the taste that sikhye is known for cannot be recreated. We have a contract with a rice producer in Incheon for Gyeonggi rice, which is much more expensive than government-stocked rice or imported rice but tastes much better. This is also why we use 100% Korean-made powdered malt oil. Two years ago, we started growing our own rice in Incheon to ensure that we use only rice of the highest quality. As for the barley needed to make the powdered malt oil, we previously used the same barley that domestic beer manufacturers use. Last year, however, we signed a contract for unhulled barley to make our sikhye better reflect the flavor of authentic traditional sikhye. Another thing we are proud of is that our sikhye is completely free of preservatives.

Another benefit of using domestic produce is that it increases the income of farmers. In one year, Sejun Food uses approximately 100 tons of rice and 300 tons of barley. Each time we sign a farming contract, we provide 50 percent as an advance to guarantee the farmer’s profit. In other words, exporting Sejun Food’s sikhye is the same as exporting Korea’s agricultural produce. We also hire people with disabilities whenever we can because I know what it is like to struggle with such limitations: due to an accident, I am hard of hearing in one ear, and my vision is quite poor. I hope to make our world a better place by making traditional sikhye.

Q. What are your plans for the future?

First, I would like to build an interactive facility for children dedicated to traditional Korean beverages. People tend to seek out the foods that they have actually experienced before. If children become accustomed to traditional beverages such as sikhye from a young age, they will continue to enjoy them in adulthood. I believe it is only when young people voluntarily seek out and enjoy traditional foods that our culinary traditions can be preserved. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, we had an iron cauldron and agunggi (traditional fireplace) in a corner of our plant where we held interactive programs for kids. Now, we are working on a larger facility designed for such programs and will be opening it in 2024.

We will also be working more actively to bring traditional Korean beverages to international consumers. In 2020, we opened a traditional beverage research center near Gonjiam IC (Haneulcheong Central Institute) where we are designing beverages specifically for foreign consumers. This fall, we will be releasing beverages made with jujubes and persimmons. I hope that these will allow Sejun Food to contribute more to the globalization of Korean food.

한국어

한국어

English

English